A significant shift is emerging in Pakistan’s religious discourse as prominent clerics, scholars, and political leaders increasingly reject extremist interpretations of Islam, instead emphasizing peace, justice, and state authority.

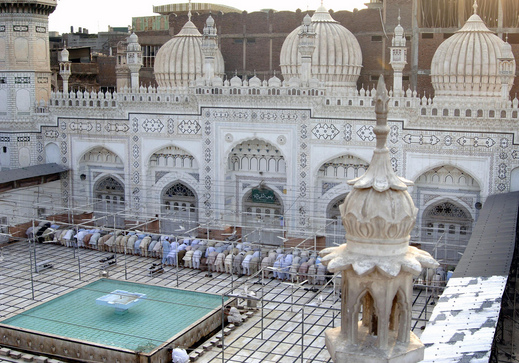

During funeral prayers in a Peshawar suburb, local imam Mufti Attiq Ahmad reminded mourners that jihad can only be declared by the state. “Islam does not allow the killing of innocent people in their own country,” he said, citing the Qur’anic teaching that killing one innocent life equals killing all of humanity. For many in attendance — some of whom had witnessed fiery jihad calls during the Afghan-Soviet war — this marked a notable change in grassroots religious messaging.

On social media platform X, scholar Hassan Ilyas rejected the Taliban’s self-proclaimed jihad. “The Taliban’s methods are not Islamic — they are a tribal mentality disguised as Islam,” he said in a video message. He stressed that Islam advocates justice, consultation (shūrā), human dignity, and adaptability to modern realities, urging the world to counter extremist narratives while respecting Islam’s inclusive principles.

Local journalist Irfan Khan echoed these sentiments, saying Pakistan must focus on education and technology to compete globally, not on restricting women’s rights. He questioned the Taliban’s narrative of holy war: “Is it the responsibility of the state, or of any individual or group? They don’t have the answer.”

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, during a media interaction in London, vowed to eliminate the resurging threat of terrorism, warning that “external elements” were working against Pakistan’s progress. He assured that the political and military leadership remained united on tackling militancy.

Respected scholars have also stepped forward. Mufti Taqi Usmani recently labelled militants as Khawarij — a sect historically known for rebellion — clarifying that Sharia does not justify insurgency against the Pakistani state. Maulana Abdullah Khalil denounced attacks on mosques, schools, and teachers as “a disgrace to Islam and humanity.”

This stance is not new: in 2014, more than 100 Pakistani scholars endorsed Operation Zarb-e-Azb as a legitimate jihad against terrorism, underlining that violent extremism has no Islamic justification. More recently, Mufti Muhammad of Jamia Tur Rasheed reiterated that rebellion against a government is impermissible in Islam, noting that declaring Muslims apostates reflects the ideology of Khawarij and Mu‘tazila, not Sunni tradition.

A senior lawyer in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Noor Badshah observed that people are now fed up with fatwas of jihad issued over the past 40 years. “People are no longer ready to trust so-called religious leaders who deceived the masses in the name of Islam,” he said, pointing to growing disillusionment with extremist interpretations.

Analysts note that this unified rejection by clerics, scholars, and state leaders reflects an evolving stance in Pakistan: Islam cannot be misused to destabilize society or justify violence against its own people.